by Stephen Young & Barbara Hockfield

Stephen Young, Senior Partner of Insight Education Systems

In visiting many companies, globally, it is striking how frequently employees wrongly categorize bad behavior as a symptom of unconscious bias, exclusion, or micro-inequity. The tendency is to use a broad brush when assessing the motivations behind behaviors that make others feel uncomfortable or demotivated.

Let’s be clear, this is not giving a pass to bad behavior. Our focus is about the accurate identification of the source of a problem and the wide range of potential solutions to address it.

You can’t fix a D&I problem by barking up the bad behavior tree!

Not only is it common to miscategorize the behaviors we observe, sometimes the overarching terms can misrepresent the action as well. One such term is microaggression.

The term microaggression has no place in the D&I world. It should be jettisoned into space and never allowed to return. First, let’s look at the root of the word aggression. Is aggression necessarily a bad thing? Many professions require aggressiveness as a cornerstone to success.

A trial attorney who isn’t aggressive is doomed. Sales or marketing professionals who lack that attribute will likely be left in the dust. In these professions, aggressiveness is not just a valued behavior, it is a critical criterion for success. Most professions require some degree of aggressiveness to prevail and succeed. So, how would the term logically apply to D&I?

Besides, what would a “micro” aggression be—a little aggressive? Isn’t there already a psych term for that—passive aggressive?

Microaggression doesn’t apply to the D&I world in any way. D&I is not about aggression, it’s about equity. In the D&I world, aggression only becomes relevant when it is applied differently to different people—when it is inequitable, and creates an imbalance of treatment.

Aggression only becomes an issue when the underlying behavior impairs another’s performance and, most important, when the behavior is based on that individual’s profile.

The more effective term for categorizing D&I issues is micro-inequities. This term focuses exclusively on matters of fairness and balanced treatment across gender, race, and other dimensions of difference, not simply bad behavior.

Why is this distinction so important? You can’t get to the root and resolution of a problem if you don’t accurately identify its source.

It’s like prescribing antibiotics to cure a viral infection. It simply doesn’t work.

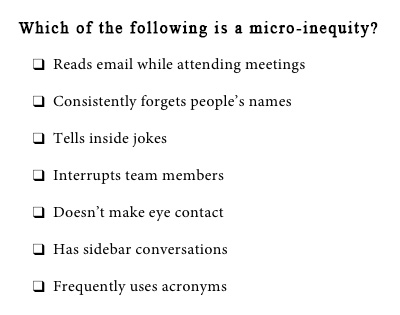

Take the quiz!

Only one of the above is a clear micro-inequity. The others may be offensive, and even impair a recipient’s performance, but they are not necessarily inequitable. They simply represent bad behavior.

“Tells inside jokes” is the only example that is a clear micro-inequity. By its very definition, telling an inside joke means that a select group is on the “inside,” while others are not. The other six examples simply represent bad or offensive behavior. In these examples, the behavior could have been sent indiscriminately and not related to a recipient’s, or group’s, identity. The behavior must be exhibited differently to different people to fall within the D&I arena and be designated as a micro-inequity.

Let’s be clear. All of the above examples have the potential for being micro-inequities, but only if it can be confirmed that the behavior is being directed based on an individual or group identity.

The following story a woman told us about interactions with her boss is a good workplace example of the danger of miscategorizing bad behavior as a micro-inequity:

The woman was in the middle of making a suggestion at a team meeting when her boss not only interrupted her abruptly, but told her how ridiculous the idea was. She was convinced the behavior was a gender-based micro-inequity.

In this particular case, I had met with the manager in question on a number of occasions and observed the same behavior directed at a wide range of colleagues. Because the woman was well-aware that gender discrimination was common in their business culture, she jumped to the conclusion that the boss’s behavior was the result of bias. However, in this example, he was an equal-opportunity jerk. Sending him to a diversity-training class to remedy the problem would likely be as effective as administering antibiotics for a viral infection.

Strong medicine, but wrong cure.

An example from our municipal justice system of a D&I offense is the preverbal hate crime. In most cases, the only distinction between a hate crime and a basic street crime is what the perpetrator was thinking. The bottle thrown through a living room window by a vandal is adjudicated quite differently if the bottle has a racial epithet written on its side.

In the workplace, we can increase our effectiveness at changing behavior and its damaging effects when we more accurately identify the nature and cause of a problem. One of the most effective solutions is to ensure that people understand the definitions of and criteria for micro-inequities, micro-advantages, micro-deceptions, and general micro-messages, and how each relates to manifestations of unconscious bias.