By Phil Chan, cofounder of Final Bow for Yellowface

Archival photos courtesy of Ballet West

In the 1950s, we see a rise in Chinese caricature in American Nutcrackers, to a trend in recent years through initiatives like Final Bow for Yellowface to improve how Asians have been represented on our stages. Here is Salt Lake City’s Ballet West in a series of historical productions of the Chinese dance in “The Nutcracker,” featuring choreography by first Willam Christiensen, then by his brother Lew Christiensen. The Christiensen brothers were responsible for America’s first production of “The Nutcracker,” celebrating its 75th anniversary this year in 2019. Photos are courtesy of Ballet West.

It’s Nutcracker time again: the season of sweet delights and a sparkling good time for all—if we’re able to ignore the sour taste left behind by the outdated and unimaginative cultural stereotypes so often portrayed in the second act of some productions. As the dance community becomes more diverse, how do the classic ballets we present need to change to be more inclusive? It’s something that, as a former dancer and dance historian, I spend a lot of time thinking about.

I was born in Hong Kong, the biracial son of a Chinese man and white American woman, and spent the first ten years of my life in a community that saw me as white. Then, my family moved to Berkeley, California, and suddenly I became the fresh-off-the-boat Chinese kid. As a result, I grew up well versed in both the slurs directed at white people in Asia and the ugly stereotypes of Asians perpetuated in America.

Agrippina Vaganova in the Chinese dance from the 1903 “The Fairy Doll”

Chinese objects and architecture were commonly available to Westerners, so many depictions of Chinese people involve parasols and pagodas (1965).

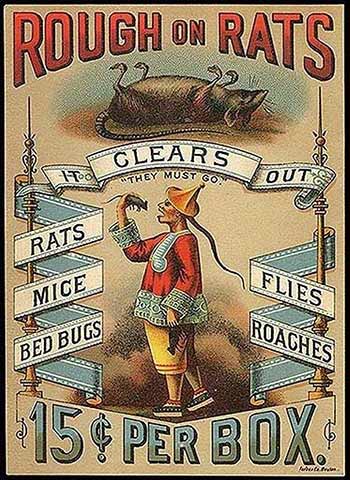

“They Must Go.” An advertisement for Rough On Rats rat poison, 1870s

A Chinese coolie with a Fu Manchu mustache with a rice paddy hat became the standard way to depict “Chinese” (1955).

Despite featuring beautiful and elaborate costumes, these early portrayals nevertheless depict inaccurate and exaggerated representations of Chinese people (1958).

Experiencing these barbs firsthand from an early age, I understood how quickly negative racial images from movies, television, and the performing arts trickled into the repertoire of schoolyard bullies. As I became an adult and a professional dancer, I began to wonder why we continued to perform caricatures of other racial groups for the sake of “preserving history” on the ballet stages where I worked.

This question came into sharp focus for me during a conversation with then Artistic Director of New York City Ballet Peter Martins, who asked for assistance modifying elements of Chinese caricature in George Balanchine’s iconic “The Nutcracker” in November of 2017. Inspired by a growing volume of emails from audience members expressing their discomfort with how Chinese people were portrayed in the ballet, Peter reached out to see how we could retain as much of the spirit of the dance as possible, while being respectful and inclusive to Asian people today.

Following a very positive conversation in which Peter made adjustments to the makeup, costuming, and choreography, I cofounded Final Bow for Yellowface with NYCB soloist Georgina Pazcoguin. We created a public pledge to eliminate outdated Asian stereotypes on our stages, in light of the field’s larger commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion housed at www.yellowface.org. The pledge simply states, “I love ballet as an art form, and acknowledge that to achieve a diversity amongst our artists, audiences, donors, students, volunteers, and staff, I am committed to eliminating outdated and offensive stereotypes of Asians (Yellowface) on our stages.”

Since then, almost every American ballet company has signed the pledge, and has leaned into the question of how we portray people of other races.

I believe there is a fear that in this new era of political correctness, some beloved dance classics that have been preserved “as is” may be deemed unacceptable to audiences today. As Sarah Kaufman of the Washington Post recently said of the visiting Mariinsky Ballet in Le Corsaire, an Orientalist work by Marius Petipa from 1856:

If the glitzy depiction of human trafficking doesn’t make you cringe, how about its parade of deplorable ethnic stereotypes, starting with turbaned Turks ogling female captives at a slave market? Popular for its flamboyance and passionate love duets, “Le Corsaire” hasn’t aged well in terms of its plot points, and its 19th-century conventions feel crass to a contemporary perspective.

But what about the dance heritage contained in the ballet itself? Is it possible to separate the artistic merit of Petipa’s choreography from the outdated representation of Arab culture? When encountering problematic portrayals of race in the classical Western canon, how do we not throw the baby out with the bathwater?

A Ming dynasty porcelain-inspired fantasy (1983)

A Chinese warrior design (1991)

In my attempt to make some sense of where these caricatures came from, I examined East/West relations at large, and broke them down into three loose periods that show how the dynamics in Asian representation changed over time. I looked at political cartoons and commentary, political treaties and immigration laws, and later, film, television, and other media to better understand what we were putting on our stages and why. To illustrate this visually, Salt Lake City’s Ballet West has graciously offered to open their archives to illustrate this historical journey.

Period I: “On Many A Vase and Jar”: The Asian as Object

Before widespread Asian immigration, Asians were often portrayed as exotic “others,” with Asian personality defined through objects, artifacts, and other secondary sources that were available. Many of these objects came to the West as a result of trade on the Silk Road, with a vogue and demand for Chinese objects in Europe dating back to 13th century. We primarily have one man to thank for this: Genghis Khan. Not only did he bring the Silk Road under a cohesive political environment (thus opening up trade in an unprecedented way), he was also the grandfather of “Yellow Peril,” having brutally conquered most of the steppes of Asia and scaring the living daylights out of Europeans at the time with the cruelty and brutality of his campaigns.

Before Asian migration the 18th century, we largely see representations of Asians in the West as possessing an elaborate and advanced culture, potentially even rivaling the West in terms of intellectual thought, technology, refinement, military might, and cultural potency.

Period II: “Yellow Peril”: The Asian as Threat

From the Gold Rush of the 1840s to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, assimilating Asians were often portrayed as caricatures, in response to rising xenophobia. Representations were informed by, or in response to, national political events like Chinese Exclusion, Japanese Internment, and the Vietnam War. Representation suddenly shifted downward in terms of class, with arts and media replacing images of exotic and regal Chinese emperors with railroad laborers, coolies, and “Chinamen.”

Certain physical caricatures of Asians by Westerners during this time have translated across film, vaudeville, and the performing arts as well. When translated to the stage, the Chinese tradition of bound feet became small shuffling steps, while the humble bow gesture became an exaggerated head bobbing, and in classical ballet, the two raised index fingers. At one time, these movements may have been attempts at imagined Chinese character dance, but over time, they’ve warped into physical caricature—exaggerated characteristics meant to create a comic, simplistic, or grotesque impression.

As many of the classical ballet works were made in Russia at the end of the 1800s, American and European caricatures of Asians aren’t featured prominently until these ballets made their way to America in the 1940s and ’50s, when we start to see caricatured Asians become the industry’s choreographic standard.

Period III: “Asian American”: The Asian as Us

With the Civil Rights Era in the 1960s, Asians began expanding self-portrayals within a new “Asian American” identity. Asians started telling their own stories and working as creatives in their own right. From playwrights like David Henry Hwang to films like Crazy Rich Asians, the idea of what it means to be Asian, and who defines that identity, occupies the artistic spirit of our current times.

This is where we are currently with Final Bow for Yellowface, questioning how Asians are defined in dance, and supporting efforts by our colleagues to see beyond outdated caricature in our classics and re-imagine them as something bigger and more inclusive.

Adam Sklute became the Artistic Director of Ballet West in 2007, and eliminated many elements of caricatured make-up and mannerisms (2011)

With the permission of the Christiensen Trust in 2013, Ballet West interpolated Lew Christiensen’s version in their production, which features a warrior battling a dragon, reminiscent of what Lew saw in San Francisco’s Chinatown while he was director of San Francisco Ballet (2018).

The make-up design is inspired by traditional Chinese Peking Opera masks, and contains sections of the dancer’s natural skin tone as part of the mask design (2018).

Conclusion

The greater longevity and relevance of the works from the Western canon depend on their ability to touch audiences around universal human truths. As a result, the arts provide a unique platform on which to build empathy for “the other” at a time when we need it most in our society; presenting outdated representations of race goes against that critical work. When arts organizations stop reviving caricature and instead offer up complex characterizations, audiences can be guided to see and appreciate the nuance in the different people around us.

Changing a little bit of head bobbing to avoid perpetuating Chinese stereotypes goes a long way with audiences; modifying makeup just a little bit to avoid caricature doesn’t make the work any less charming. Small updates to refresh portrayals of race ensure that classic works like The Nutcracker stay alive and become bigger than their creators intended—something for everyone to enjoy year after year around the holidays. Isn’t that a better way to tell a story?

Phil Chan

Phil Chan is the co-founder of Final Bow for Yellowface and currently serves as the Director of Programming for IVY, connecting young professionals with leading American museums and performing arts institutions. He is a graduate of Carleton College and an alumnus of the Ailey School. As a writer, he served as the executive editor for FLATT Magazine and has contributed to Dance Europe Magazine and the Huffington Post. He was the founding general manager of the Buck Hill Skytop Music Festival and the general manager for Armitage Gone! Dance and Youth America Grand Prix. He served multiple years on the National Endowment for the Arts dance panel and the Jadin Wong Award panel presented by the Asian American Arts Alliance, and is on the advisory committee for the Parsons Dance Company. He also serves on the Leaders of Color steering committee at Americans for the Arts.