By Amanda J Felkey, PhD

Thousands of companies in the U.S. and around the world are trying to make their workplaces more inclusive. Evidence that a sense of belonging can bolster effective teamwork, fuel innovation and boost profits has prompted many companies to devote resources to enhancing inclusion. The majority of fortune 100 companies have created a position in their C-suite, Chief Diversity Office (CDO), indicating they are committed to making change in DEI in their organizations.

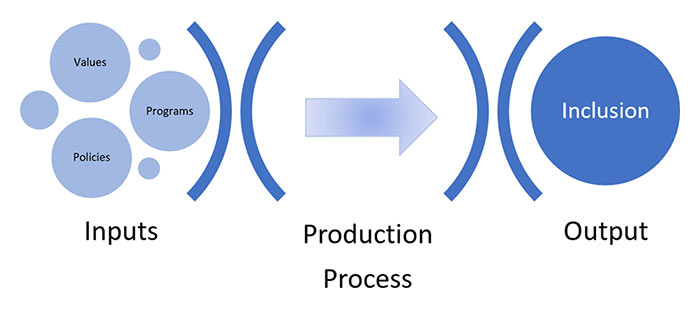

Reportedly, eight billion dollars annually are directed at “producing” inclusion. CDOs, task forces and directors are charged with making inclusive environments. They identify and encourage inputs in such a way that the production process creates inclusion as an output. Figure 1 illustrates how producing inclusion might happen and demonstrates that the “producers” of inclusion change policies, offer programs or even reconsider company values to make their organizational culture more inclusive. Notably, companies tend to focus most of their efforts on programming (trainings, speakers and workshops) as it is a cost-effective way to convey information to many.

Figure 1. Inclusion Production

With all the effort and money targeted at making workplaces more inclusive, it is important we think critically about what the inclusion production function looks like. Understanding how organizations become inclusive will help us more effectively create a sense of belonging in every workplace.

Production Functions and The Law of Diminishing Returns

Production functions universally have the same shape, illustrated in figure 2. Whether we are considering project management, product development or other business endeavors, production functions increase but at a decreasing rate.

Consider a production example with which we can all relate— making dinner. Figure 2 demonstrates that as there are more people in the kitchen making dinner (measured on the horizontal Figure 1. Inclusion Production Figure 2. The Making Dinner Production Function axis), more dinner will be made (measured on the vertical access). But let’s take a closer look at how production behaves. In box A, you make dinner yourself and you can see adding one person makes a certain amount of dinner (identified by the size of the box). If you ask a friend to make dinner with you, adding that friend’s labor will yield less than twice as much dinner, likely because you were catching up about your week and a little less productive than when by yourself. With several friends at a dinner party, box C, the last friend you invite yields even less additional dinner. There is even the potential to have too many cooks in the kitchen and more people actually decreases production, box D. You are waiting in line to use the oven and bumping into your dinner party guests while trying to prep food. What can be done? You need a bigger kitchen—you have to increase another input because adding more people will not make more dinner.

Figure 2. The Making Dinner Production Function

This dinner-making example demonstrates what economists call the law of diminishing returns. Since the mid-1700’s economists have identified that production, of any kind, will exhibit diminishing returns. That is, when you increase one factor of production, leaving the others constant, each additional input unit will yield less production than the previous.

It makes sense the inclusion production function exhibits diminishing returns. Consider the most utilized input, programming. When individuals attend their first training, they learn a lot of new information, are inspired to act more empathetically and may even feel invigorated about equity. In their second program people learn a few new useful facts, and are reminded that inclusion is important. A few programs down the road and people are not learning anything new, and their attendance at programs and workshops could adversely affect inclusion by crowding out individual effort, amplifying overconfidence and even generating annoyance.

Inputs to Inclusion Production

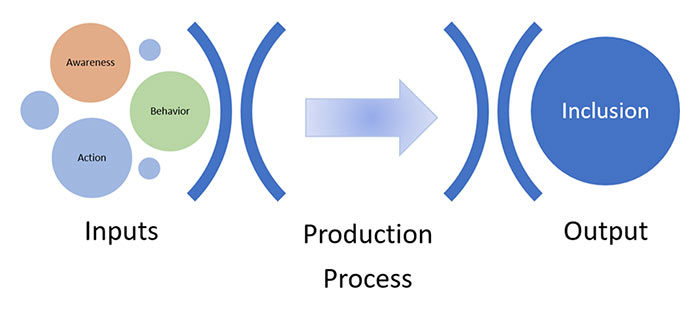

When analyzing the inclusion production function, it is useful to map the instruments we use to make change into the elements that matter to generating inclusion. That is, instead of thinking about policy versus programming, we should consider what these instruments yield that actually leads to inclusion. A better categorization is depicted in figure 3. The actual inputs to inclusion production are awareness, action and behavior. While programming generally promotes only awareness, there could be programs that also instigate action. Such programs would then be a different input into inclusion production.

Figure 3. Inputs for Inclusion

To date, most inclusion efforts have been focused on awareness, yet myriad research tells us that these are the least effective at generating an inclusive environment. The most successful programs are those that require action. A 2016 study by Frank Dobbin and Alexandra Kalev considered diversity efforts at 829 large and midsize U.S. firms and found the most impactful initiatives were mentoring and employing a diversity task force, both strategies associated with action.

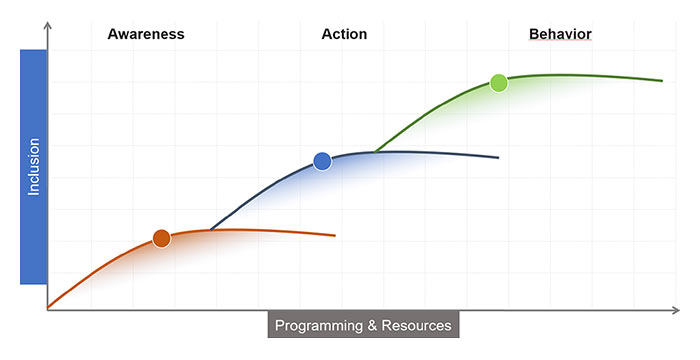

By moving beyond awareness- based programing, employing other inputs or even finding new ones, like those that induce action and behavior change, companies can create inclusion production that goes beyond the limits of the diminishing returns of awareness. As demonstrated in figure 4, when an organization reaches the limits of awareness-based inputs, they can couple those with strategies focused on action to enhance inclusion. Moving beyond action into behavior change can catapult inclusion production even more.

Figure 4. Combing New Inputs

As you can see, there are new frontiers when organizations strategically alter complementary inputs. There may still be benefits from programming, but only if programming is coupled with other inputs that focus on action and behavior. Focusing on awareness alone is like having one kitchen, including action initiatives is like having two kitchens and adding behavior change as an input in your inclusion production function will be like having three kitchens.

Behavior change is the only way to produce a genuinely inclusive environment. The problem is, behavior change is hard, especially when it comes to inclusion. Even if someone has the desire and necessary ability to act more inclusively, behavior change may still be difficult. Behavioral scientists would warn us that time inconsistent preferences and unconscious biases can thwart our efforts to behave more inclusively. Even though behavior change initiatives may take substantial time and effort, they are worth the resources. New behaviors of inclusion are necessary to push the boundaries of inclusion.

Going Beyond the Limits of Programming

Some organizations are beginning to shift their focus to behavior-based inputs as they produce” an inclusive environment. For example, Belonging at Cornell, a new initiative launched on the Ithaca campus last fall, provides a framework that goes beyond programming. While Belonging at Cornell is impressive in many ways, most remarkable is its aim to go beyond programming. Angela Winfield, Associate Vice President for Inclusion and Workforce Diversity, says “the Belonging at Cornell framework [is a] shift from awareness to awareness coupled with individual action and behavior change.” This is exactly the shift that is making inclusion a reality at Cornell.

A few months ago, The Inclusion Habit (published in the Fall 2019 edition of this journal), an evidence-based solution designed to make behavior more inclusive, was launched at a Fortune 100 financial services firm. The Inclusion Habit uses a platform called ProHabits to provide daily small commitments aimed at understanding biases and their sources, dispersing with the negativity associated with unconscious biases, practicing thinking more deliberately, reprogramming incorrect intuitions about others and becoming more empathetic. Despite the COVID-19 transition to remote work during this pilot study, a qualitative analysis of participant comments and stories reveals they feel more connected. In surveys, 70% of participants report practicing more inclusive behavior. Participants also indicated they were reflective and mindful.

Conclusion

While inclusion programming may be a cost-effective way to raise awareness about diversity issues in the workplace, the change it creates in actual inclusiveness is minimal. Programming has limited returns and creates false confidence. In fact, its ineffectiveness and byproducts may even adversely affect the organization’s culture—too many DEI programs is like too many cooks in the kitchen. Only by moving beyond mere programming and focusing on individual action and behavior can organizations truly make meaningful strides toward a genuinely inclusive environment.

Dr. Amanda J Felkey

Amanda J Felkey holds a PhD in behavioral economics from Cornell University and has won several awards for her publications about her decision-making research. She currently teaches at Lake Forest College, where she is chair of the Department of Economics, Business, and Finance and chair of the Entrepreneurship and Innovation Program. Notably, she wrote a paper (with Kaushik Basu) about multiple equilibria, which was published in Oxford Economic Papers.