By Amanda J Felkey, PhD

To date, companies have relied heavily on programming—speakers, workshops, and training sessions—to raise awareness about diversity and enhance inclusion in their workplaces. The Society of Human Resource Management reports that diversity department budgets, among companies in the Fortune 1000, range from $30,000 to $5.1 million, with an average of $1.5 million, annually. A report by Axios revealed that Google has spent more than $265 million since 2014 to bolster their diversity initiatives and enhance their reporting of diversity outcomes. Researchers estimate U.S. companies spend more than $8 billion annually on diversity, inclusion, equity, and belonging efforts. Almost half of these departments report that their budget is spent on training programs. In spring 2018, New York City budgeted $23 million to be spent on bias training for public school employees.

While programming is well intended, and a cost-effective way to convey information to large numbers of people, it is limited in its ability to effectively enhance inclusion because of how we learn. In fact, it may even thwart our inclusion efforts, as it fosters overconfidence about our inclusion competencies and crowds out individual efforts to be more inclusive.

Forgetting What We Learn

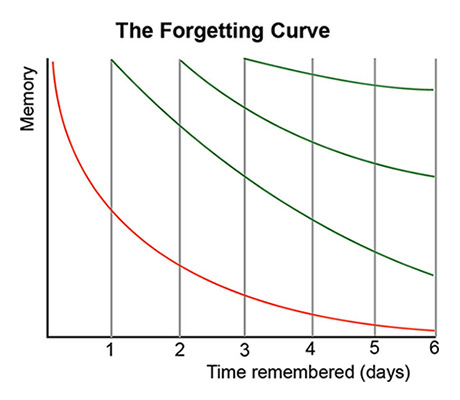

People quickly forget what they learn. In 1885, Hermann Ebbinghaus, a German psychologist, developed the forgetting curve to demonstrate the exponential rate at which individuals forget information if there is no effort made to practice or retain it. The red line in figure 1 shows how Ebbinghaus predicted information is forgotten after first exposure. Without effort to retain the new information, it is nearly all forgotten within a week. He extended his study to examine how effort to retain the new information in the form of practice after first exposure can mitigate the forgetting effect. The forgetting associated with practicing the information one, two, and three days after first exposure is depicted by the green lines. Several researchers have confirmed that the forgetting function takes this exponential shape and that we forget much of what we know relatively quickly. Recent studies demonstrate that the effects of mass communication of persuasive ideas are subject to rapid decay (Hill et.al., 2013; Murre & Dros, 2015).

Figure. 1

A typical representation of the forgetting curve. (Image by Icez, from the Wikimedia Commons.)

The fact we forget so much so quickly does not bode well for the programming efforts we hope will revolutionize inclusion in the workplace. The harsh reality is that, even if all parties—the programmers and attendees—are well intentioned, most people will forget the majority of the information conveyed. No matter how dynamic the speaker or how inspirational the message, information we do not diligently work to retain will mostly be forgotten. The fact that our workdays are inundated with emails, slack messages, and social media alerts makes it difficult to find available time and effort to follow up and work toward retaining the important inclusion message.

People also forget more quickly information that is contrary to their current beliefs and attitudes. In a 1940s study, a story of male-female conflict, in which the woman was portrayed as superior, was presented to high school students. The young men forgot the content more rapidly than did the young women over a four-week period (Clark, 1940). Another study, during the same decade, gave pro- and anti-Communist paragraphs to individuals with different political views. The subjects retained information that aligned with their political leanings for longer periods of time (Levine & Murphy, 1943). This suggests that those who could benefit most from inclusion programming are those who will forget its content more swiftly.

The limits of DEI programming are exacerbated by the way companies naturally scale these efforts. Companies start with small interactive workshops to create buy in and due to costs move quickly to speakers and training sessions that focus on conveying large amounts of material to as many people as possible. Even cheaper per person, the next step is a move to online training, where companies hope to engage even more individuals in learning about inclusion. As DEI programming progresses along this path its impact declines. There is a large body of research on teaching modalities and learning that boils down to what Mahatma Gandhi told us, “An ounce of practice is worth more than tons of preaching.”

Programming and Overconfidence

Overconfidence is well documented and practically universal. People think they can spell better than they actually can—they claim they are 100 percent confident, while they are only correct 80 percent of the time. People think they are above average drivers—93 percent of Americans think they are above the 50th percentile when it comes to their driving. People think they are great leaders—98 percent of high school students believe they are above average leaders. People tend to think they can finish tasks in a shorter time than it actually takes them—they overestimate how diligently they will work on tasks. People are overconfident in their investing—a survey of 300 professional fund managers found 26 percent believe they are average and 74 percent believe their performance is above average. Overconfidence is bolstered and reinforced by our tendency to blame our failures on factors outside our control, while attributing our successes to our own decisions and actions.

Among the three types of overconfidence, overprecision is the most important to the evolution of inclusivity. Overprecision is the propensity to put undue confidence in one’s beliefs. This means if our brain has a bias about other people, we overestimate the probability that any given biased thought is correct and are thus less likely to acknowledge that bias.

For example, consider the stereotype that blondes are unintelligent and the reality that intelligence is independent of hair color. If this is one of your unconscious biases, then it will affect your assessment of blondes and the overprecision bias will make you all too confident in your quick assessments. The independence of intelligence from hair color means half of all blondes have above average intelligence. The stereotype that blondes lack brains would suggest that you associate a probability of less than half with any blonde person you meet being intelligent. This means that when you meet your next blonde coworker, you will unconsciously adjust your assessment of the person’s intellect downward. Because you are also susceptible to the overprecision bias, you will be confident this biased assessment is unbiased.

Overconfidence leads to suboptimal outcomes for both the individual and society. Investors who are overconfident have the greatest propensity to trade because they believe they can pick the next great stock and outsmart the market. Research has found the underperformance of these overconfident traders is three times as large as average underperformance among all traders (Odean, 2000).

In the same way, overconfidence leads you to firmly believe your blonde coworker is not terribly smart, which justifies in your mind marginalization during business interactions. With your overconfident misconception that your coworker is less intellectually capable than average, you will be less likely to seek meaningful collaboration, less likely to assign difficult tasks, and less likely to invest in that coworker’s success. All these actions, which adversely affect your coworker, are the result of society telling you blondes are not so smart and your overconfidence in that bias.

A more pungent example of how our biases and overconfidence comes from the provocative book, White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk about Racism, by Robin DiAngelo. She asserts that white progressives do the most damage to people of color. DiAngelo defines white progressives as white people who believe they are less racist and more enlightened about race than others—they are white people who believe they “have arrived.” They are individuals who are overconfident that they are bias-free and unapologetically continue to act according to their biases. The overconfidence of white progressives makes them believe they do no harm to others through unconscious bias, while in actuality, their biases remain, and they have simply ceased to acknowledge they are there.

Unfortunately, DEI programming and unconscious bias training can exacerbate overconfidence and unintentionally thwart inclusion. Stuart Oskamp, an emeritus professor at Claremont Graduate School and an expert in attitudes and attitude change, conducted a study demonstrating increased exposure to information does not necessarily make people more accurate. However, it does increase their confidence in their accuracy.

He asked subjects to read a case study in sections and after each section, to answer questions about the case and document how confident they were in their answers. Additional information about the case systematically made individuals more confident in their answers. Yet their accuracy was largely unaffected. Their confidence increased from 33 to 53 percent, while their accuracy remained statistically consistent at 30 percent. Oskamp’s study demonstrates that more information may change nothing but overconfidence.

If DEI training does not actually change behavior or biases, but merely makes people more confident in their behavior, then the training accomplishes nothing more than making people feel better about their exclusion. In the case of DiAngelo’s white progressives, it is possible that inclusion training and DEI programming are what led them to feel so confident in their enlightenment. Training may have fostered a false sense of confidence about inclusivity. With the false confidence that their actions are now in line with their inclusive intentions, individuals will be less likely to notice and examine their exclusivity in daily practice and it will perpetuate.

Policy and More Overconfidence

Confidence and success go hand in hand. According to the American Confidence Institute, we are attracted to confidence for several scientific reasons, and this attraction may be the reason confident people are so successful. When a confident person comes up for promotion, our attraction to their confidence may make their promotion more likely. The halo effect will lead us to believe that because this person is confident, they are also smart and have other specific characteristics that will make them successful in the more demanding role. So confidence can cause success.

As illustrated in figure 2, the causality may run the other way, where success breeds more confidence. Recall my earlier discussion of our tendency to attribute success to our own decisions and actions and attribute failures to circumstances. Since our leaders have had more successes, they have had more opportunities to attribute achievement to their own capabilities. As a result, their confidence has grown at an above average rate.

Figure. 2

Regardless of whether success causes confidence or vice versa, the association between the two is theoretically solid and well documented. This means overconfidence is more prevalent among our leaders, so they will be more prone to overconfidence in their judgments and decisions.

Our attraction to confidence supports a social mechanism by which those that are most affected by the overconfidence bias are those in the most powerful positions in our society. This means our organizations’ leaders are the most overconfident of their inclusivity, and efforts to combat exclusion may be hindered at the policy level. Overconfident individuals will not prioritize continued change in the realm of inclusion because they are overconfident that existing changes in the area of inclusion are already the best and most correct.

A 2006 study by Gokul Bhandari and Richard Deaves explored whether overconfidence varies systematically among people. Focusing on whether someone believes he or she is correct, Bhandari and Deaves measured certainty, knowledge, and overconfidence among 2,000 Canadian investors. They found that highly educated males are most susceptible to the overconfidence bias. While there is no distinguishable difference in knowledge, the average certainty level among men is 46 percent and only 37 percent among women.

The data also shows that overconfidence is significantly more likely among individuals with higher incomes. The likelihood of overconfidence among those who make more than $100 thousand a year is 81 percent, while the likelihood among those making no more than $50 thousand is 68 percent.

In an analysis that accounted for all the measured demographic variables simultaneously, they isolated the potential effects of each variable on making an individual more certain and even overconfi-dent. Bhandari and Deaves found that being male, being older, having more education, and having a higher income are all significantly associated with higher levels of certainty and a propensity to be overconfident. Intuitively, it makes sense that these characteristics affect certainty and overconfidence in a positive way, but when it comes to inclusion innovations, this finding is troubling.

If our policymakers are overconfident, they are more likely to have full confidence in policies they have already endorsed, even if those policies are based on a limited worldview. Their confidence will make them less likely to reconsider and revise current policies because they hold the overconfident belief that what they have already designed or endorsed is correct.

Dr. Amanda J Felkey

Dr. Amanda J Felkey has a Ph.D. in Behavioral Economics from Cornell University and a Diversity and Inclusion Certificate from eCornell. She has authored award winning publications, is actively researching unconscious bias, has 20 years of experience in decision-making research and 15 years of experience in curriculum design. Felkey currently teaches at Lake Forest College where she is Chair of the Department of Economics, Business and Finance and Chair of the Entrepreneurship and Innovation Program.