By Peter Trevor Wilson

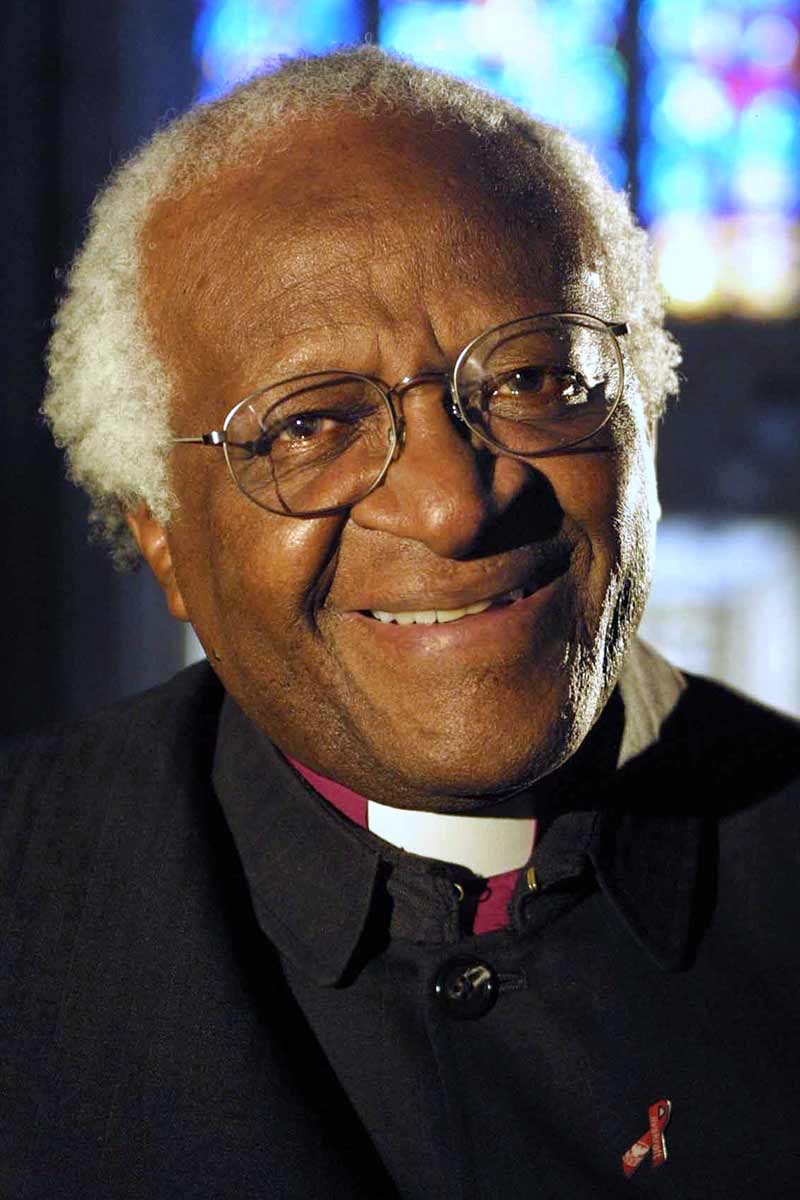

One of the most frequently asked questions since the publication of my last book is regarding the origins of the phrase human equity. Where did it come from? The truth is that human equity started with a slip of the tongue in South Africa almost two decades ago in a speech by the late, great Reverend Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

The Arch was giving a speech on employment equity, the legislated equal opportunity program used in Canada and South Africa to help women, people of color, people with disabilities, and indigenous communities. Early in the speech Tutu mistakenly used the term “human equity” instead of “employment equity.” He quickly corrected himself and barely noticed the mistake. But a quiet voice whispered to me “human equity is a thing. Tutu doesn’t know it and you don’t know it but if you stay with it, you will find out what it is.” The only thing the little voice did not say was, “By the way, it will take more than a decade to figure it out.”

When my human equity book was finally finished in 2013, Tutu generously offered to provide a foreward. We saved the foreward he provided for the South Africa version of the book, so it was never published. However, it was very powerful. He pointed out that South Africa had lost ground under Apartheid and as such, had to redouble efforts to build a nation by optimizing on all available talent. In other words, post-apartheid South Africa had to practice human equity.

Tutu pointed out that, not unlike the goal of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), the human equity book provided a prescription for moving forward in establishing a viable alternative to the notion of “turning the tables.” (i.e., “You had your turn white man, and now it’s our turn”). He stated that if one agrees that a country must be able to compete on a global scale, it follows that that country must respect, appreciate, and utilize all of its human capital. Tutu also pointed out that South Africa needed a system that was inclusive of those who were its previous beneficiaries (i.e., the white population). No easy task.

Tutu’s never-published foreward describes what happens when the diversity that increasingly marks our societies, intersects with the requirements for succeeding in a world whose marketplace is increasingly without borders. He pointed out that human equity goes beyond superficial differences like gender and race to look at the full range of talent, skill, and intangible strengths of all individuals. He pointed out that human equity meant removing the overt and systemic barriers to talent optimization. He believed that this would allow the new South Africa to leverage the contributions of all skilled, talented, and educated citizens—a fundamental precondition for global success.

Tutu added something else to the human equity puzzle—something priceless, for which I will be forever indebted to him. He intuitively recognized that in order to practice human equity there needs to be an acknowledgement of our basic human frailties. He showed that, like the TRC, human equity must be based on the ancient, brilliant African tradition of ubuntu—the spirit of forgiveness. Ubuntu provided the spiritual foundation for the work of the TRC, which could now be used by human equity.

As Tutu said in his own book, No Future Without Forgiveness, “If someone steals my pen and asks for forgiveness, I can choose to do so. But unless he returns my pen, I remain unable to write.” Tutu believed that human equity could provide the pen to construct a tangible roadmap for achieving inclusion for all, including all the great minds wasted under Apartheid.

I am forever grateful to you, Arch, for your great wisdom, inspiration, and guidance.

Peter Trevor Wilson

Peter Trevor Wilson is Global Human Equity™ Strategist, Toronto, ON. He is a dynamic speaker, a visionary thought leader and a global diversity and Human Equity™ strategist. Wilson is founder and president of TWI Inc