By Jon L. Erickson

Over the past four years, the number of African American and Asian students taking the ACT® has increased by 20 percent, and the number of Hispanic students taking the ACT has nearly doubled. This is consistent with projections from the National Center for Educational Statistics, which from 2009 to 2020 expects white college and university enrollment to increase by 1 percent, African American and Asian enrollments to expand by 25 percent each, and Hispanic enrollment to surge by 46 percent.

That’s the good news. The not-so-good news is that according to ACT’s 2013 Condition of College and Career Readiness report, only about one-fourth of ACT-tested high school graduates met all four of the ACT College Readiness Benchmarks. A benchmark is an English, Mathematics, Reading, or Science score representing the achievement necessary for students to have a 50 percent chance of obtaining a B or higher, or about a 75 percent chance of receiving a C or higher, in a corresponding credit-bearing first-year college course.

Slightly more than 40 percent of Asian students met all four benchmarks compared to 13 percent of Hispanic students and 5 percent of African American students. Fewer than half of students from all backgrounds met all four benchmarks. For students of any race or ethnicity who lack the financial or family resources to overcome educational obstacles, the challenges can be particularly fierce.

For example, when students require remedial education, it often takes more time to graduate, which means more money for tuition (and books, fees, transportation, room and board, and student loans). More time means more opportunities for “life” to interfere with degree completion. More time to learn also means less time to earn, and even when students do graduate, less time to benefit from the higher salaries college degrees often command.

WHAT TO DO

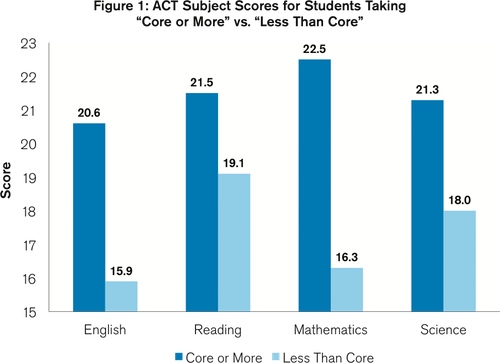

Across all ethnic groups, the most important strategy for increasing college and career readiness is to increase the number of students completing a rigorous high school core curriculum, defined by ACT as four years of English and three years each of mathematics, social studies, and science. The positive effects of completing or exceeding the ACT-defined core curriculum are apparent. According to ACT data, on the:

- ACT English Test, 67 percent of students who took four or more years of English courses met the English benchmark. Only 36 percent of “less-thancore” students did.

- ACT Reading Test, 46 percent of students who completed three or more years of social studies courses met the benchmark, compared to 32 percent of “less-than-core” students.

- ACT Mathematics Test, 46 percent of students taking three or more years of mathematics achieved the benchmark, compared to only 7 percent of “less-than-core” students.

- ACT Science Test, 40 percent of students taking three science courses in high school met the benchmark, but only 17 percent of the “less-than- core” students.

Just as important, when students completed the recommended core (or more) coursework for a subject, they achieved higher scores for that subject, indicating higher levels of mastery. Even a single point on the 1 to 36 ACT scale is meaningful. As depicted in Figure 1, on average students who completed:

- Four or more years of English scored 4.7 points higher on the ACT English Test than studentswho took fewer than four years.

- Three or more years of social science scored 2.4 points higher on the ACT Reading Test than students who took fewer than three years.

- Three or more years of mathematics scored 6.2 points higher on the ACT Mathematics Test than students who took fewer than three years.

- Three or more years of natural science scored 3.3 points higher on the ACT Science Test than students who took fewer than three years.

DEMOGRAPHIC IMPLICATIONS

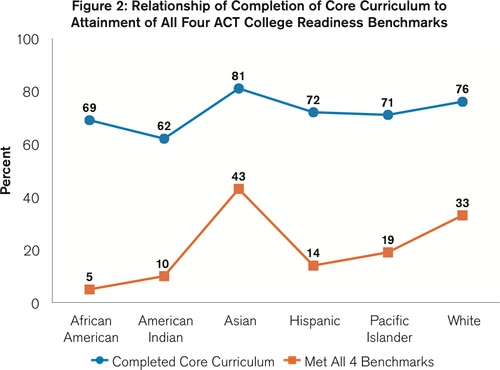

For ACT Composite test scores (the average of a student’s English, mathematics, reading, and science scores), African American students who completed the core scored about two points higher than those who did not; American Indian, Asian, and Hispanic students scored more than two points higher; and Pacific Islander and White students scored three points higher.

That said, what is inconsistent across groups is the proportion of students completing the core. Groups with higher core completion rates also tended to have more students who met all four ACT College Readiness Benchmarks, as shown in Figure 2.

ASPIRATIONS AND ATTAINMENT

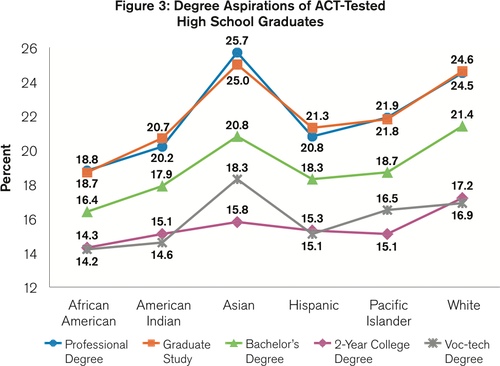

For some students, perceptions of what is possible may affect their academic decisions.

If students believe selective colleges are unaffordable because of their high “sticker prices,” they may not apply to them, unaware that these schools’ financial aid resources may reduce students’ net costs to amounts lower than at less selective schools. As a result, students who think they’re destined for less selective schools may avoid the most rigorous high school courses that would best prepare them for postsecondary success.

No matter their reasons, differences in aspirations across demographic groups are apparent, as shown in Figure 3. Broadly speaking, ethnic groups with higher academic aspirations tended to be those who completed the ACT-recommended core curriculum—a short-term accomplishment that also makes long-term goals more likely to be achieved.

POLICY AND EDUCATIONAL IMPLICATIONS

To encourage all students to match their aspirations with their achievements, policymakers and educators should:

- Implement standards consistent with college and career readiness, such as the Common Core State Standards.

- Ensure access to rigorous courses. Quality courses are even more important than quantity; they help students succeed after high school without remediation.

- Monitor early and intervene immediately. The earlier issues are identified and addressed, the more quickly students can be brought back on track for success.

- Create a culture of postsecondary success. Motivation matters. A compelling vision for life after high school affects decisions made during high school—even decisions made many years before.

DIVERSITY-AND CONSISTENT EXCELLENCE

Diversity is one of our nation’s unique assets, but our vitality also depends on how well we prepare all students for tomorrow’s opportunities. Uneven academic achievement must be replaced by consistent educational excellence.

In support of this outcome, ACT has introduced ACT Engage®, which assesses student motivation, social engagement, and self-regulation—all behaviors that affect academic success. In 2014, ACT will begin rolling out ACT Aspire™, which will help students, parents, and teachers chart student progress as they prepare for high school, college, and career. ACT has also recently unveiled ACT Profile, a free social media site where students can take the ACT Interest Inventory and receive reliable college and career guidance based on their abilities, interests, and values.

From kindergarten through career, ACT is committed to its nonprofit mission: “Helping people achieve education and workplace success.” In the same spirit, students from all backgrounds deserve to be educated in an environment in which their aspirations for excellence are supported,nurtured, expected—and achieved.

Jon L. Erickson is president of the Education & Career division of ACT. The nonprofit organization responsible for the ACT test—the college admissions and placement test taken by more than 1.6 million high school graduates every year—ACT provides more than a hundred other assessment, research, information, and program management services for education and workforce development.