Part III of the series The Illusion of Inclusion

By Helen Turnbull, PhD

Is it realistic to believe that we can keep it from happening or manage our way out of it? Or is affinity bias such an entrenched part of human behavior that we cannot hope to change it?

If I were to make a hierarchical list of unconscious biases and their impact on retention and the talent pipeline, “Affinity Bias” would surely be a top contender. It is true that affinity bias is most often defined in the context of the hiring process—when interviewers show a preference for candidates who are similar to themselves—but I would argue that it has much more wide-ranging ramifications.

Understandably, corporate hiring practices are set up to find people who are a “good fit” for the organization, people who will bring value to the team. These requirements cause us to look for candidates who are not only professionally skilled, but are also people we can relate to. However, as corporations seek to recruit and retain diverse candidates, they are turning the spotlight more and more on our natural human tendency towards affinity bias—towards hiring (and promoting) in our own image. To mitigate affinity bias in the hiring process, many corporations have engaged diverse recruitment panels to add different perspectives to the hiring discussion. Some of my clients are removing names from resumes during the first round of the recruitment process to limit initial bias. So why is it that, simultaneously, hallway discussions about reverse discrimination, political correctness, and whether or not we have gone too far with the D & I agenda, continue?

In truth, we all have a natural propensity to want to be around people we can relate to and, if we are honest, have a really hard time contemplating the contrary. If affinity bias means being biased towards “people who make me comfortable” or “people who are like me,” then, surely, somewhere tucked in the recesses of our minds are the shadows of these thoughts—“people who make me uncomfortable” and “people who are not like me.” And, let’s be honest, who in their right mind wants to surround themselves with people who make them uncomfortable?

When we talk about affinity bias in the context of the workplace, the subtext of that conversation implies that we are asking the dominant culture—namely white men—to recognize that we need more diversity. That may be accurate, but it is only one piece of the story. We all have a predisposition towards affinity bias, regardless of our race, culture, gender, or other diversity group membership(s). Affinity bias is not the exclusive right of the dominant culture, and yet there exists an interesting and paradoxical phenomenon in that it is still much more difficult for people from subcultures to hire or promote people in their own image (a subject we will return to in the next article).

Part of the human condition?

Affinity bias shows up in all kinds of subtle ways—often unnoticed—and can impact our choices of whom to trust. For example:

A few weeks ago I had occasion to call a customer service number for assistance with one of my recent purchases. The young woman who answered the phone had a shrill, high-pitched voice, and spoke quickly and incessantly in a monotonous tone, suggesting to me that she was reading from a script. No matter what question I asked her, she repeated the same scripted response. My blood pressure was rising and my patience was wearing thin. No matter what I said, I could not get her to understand what I needed. I finally asked her where she was located, and she said, “The Philippines, but I am very well trained.” I detected some, perhaps understandable, defensiveness in that answer; however, I hesitated to tell her my inner thoughts at that time (being that she was indeed very well trained to read the script, but only the script). Instead I asked to be put through to a supervisor. A few minutes later I heard an American voice: “Hello, this is Mary. How can I help you?” I asked her where she was located, and she said she was in Indiana. My breathing began to normalize, I started to feel more relaxed, and I began my story again—feeling more confident that I was “in good hands” and, this time, would reach a satisfactory resolution.

There are many ways we could unpack this story. We could focus on customer service and discuss the vagaries, and rights and wrongs, of off-shoring; or whether the customer feels heard and the impact of language, accent, tone of voice, and pace of speech on our ability to listen. However, as my main point of focus is on affinity bias, I found myself wondering how often I notice that I am breathing easier around people who are like me. Conversely, I wondered how aware I am of the physiological changes that occur inside me, when I am around people who are different from me, without even realizing they are happening. I venture to suggest that this almost unconscious physiological reaction is impacting trust, inevitably affecting the quality of my relationships, and, perhaps, even having a detrimental effect on the decisions I might make about projects and assignments.

If you accept my premise that affinity bias is part of the human condition and is not going to go away, then the question becomes, “What can be done to ensure that we all behave in an inclusive manner and value diversity?” Results from one of my assessment tools, the Inclusion Skills Measurement (ISM) Profile, suggest that managing conflict across differences and having integrity with our own difference are two areas where we often find the largest skill gap. We are not as comfortable in managing the boundaries across differences as we tell ourselves we are.

Managing affinity bias seems to hold the same challenges as being an inclusive leader in that, in order to breathe more easily with people of difference, we need to get to know them and become comfortable with them. We will never totally rid ourselves of affinity bias, so what we need to do is feel affinity for more people of difference. Perhaps a good way to start would be to pay attention to our reactions and learn to breathe more easily when we are interacting across differences.

The Illusion of Inclusion: Helen Turnbull, PhD

Helen Turnbull, PhD

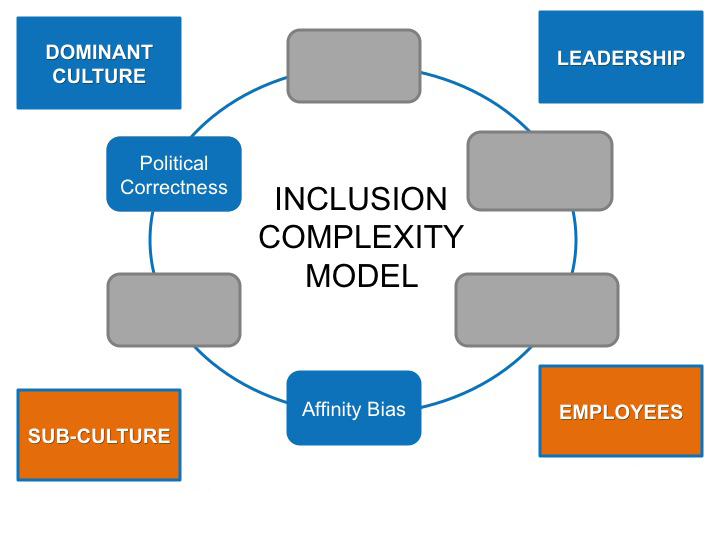

Dr. Helen Turnbull is the CEO of Human Facets LLC and a world recognized thought leader in global inclusion and diversity. She is a member of the Academy of Management, American Psychological Association, American Sociological Association and American Society for Phenomenology; The Neuro-Science Institute for Leaders and the OD Network. Her latest book is “Blind spots: A conversation with Dr. Turnbull about Unconscious Bias”. In May 2013, she spoke at TEDx on “The Illusion of Inclusion” and has recently developed a new model on the complexity of embedding an inclusive workplace culture.

Dr. Turnbull has identified a critical challenge my clients face. And the bias that concerns me the most is an affinity for someone who communicates and makes decisions in a way similar to the executive who is hiring. Diversity in how leaders make decisions is an advantage on a leadership team not an impediment.

We need to notice and then temporarily break the automatic association of different or unfamiliar = uncomfortable (or wrong or unpleasant). Or better yet, make a habit of it! Easier said than done. Great post, Dr. Turnbull.

Doctor Turnball makes a good point. It is impossible to get rid of affinity bias of 100%. However, we can always try to feel an affinity for people who are different like us so that we can accept them for who they are.

Thanks for sharing the post and have a great day.

I love your ideas and support every word.