By Grace Austin

The University of California at Berkeley has a long and storied history of dissident voices on campus. Established in 1868 near the San Francisco Bay, the public research university currently counts more than 35,000 enrolled students. It is the oldest of the ten major campuses in the University of California system. In addition to producing countless Olympic athletes, Nobel Prize winners, and Academy Award winners, Berkeley researchers have been credited with finding six chemical elements on the periodic table.

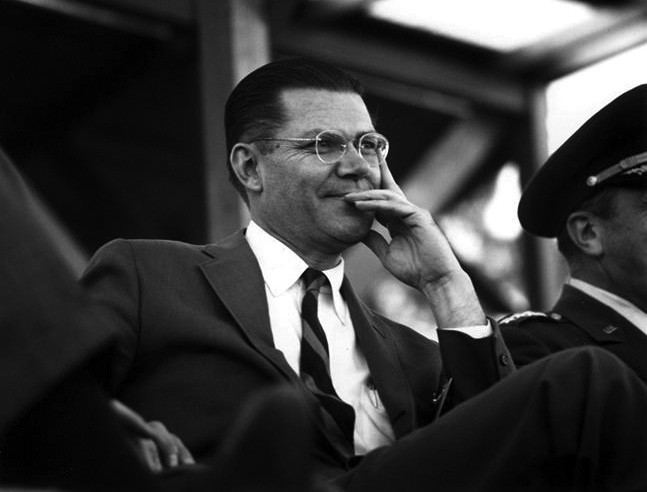

Named in honor of a philosopher, major donations from the Hearst family more than a century ago helped develop the Berkeley campus. Now with a $3.15 billion endowment, the university has received funding recently from BP, Dow Chemical, and the Hewlett Foundation. Consistently ranked one of the top schools in the world, Berkeley carries both prestige and celebrity—Apple cofounder Steve Wozniak, actor Gregory Peck, and World Bank leader Robert McNamara are all notable alumni.

Diverse Thought and People

Berkeley has long been known for its ample resources and open culture—something which draws a

wide array of people from diverse backgrounds.

A majority of women comprise the undergraduate population, although the gender ratio is relatively even. Asian Americans represent a plurality of the population, with 42 percent of the undergraduate student body. Hispanics make up 12 percent of the student population. While that may seem high, in comparison, California’s population is 35.9 percent Hispanic. Similarly, the African American population is low, a little over 4 percent. This underrepresentation has been widely criticized at a school not only known for its prestige and academic focus, but its history of diversity of thought and people. Considered to be the premier university in California, not being reflective of the state’s demographics has been an issue for the institution in recent years.

Much of this comes from the difficulty of admissions. (The average GPA of 2010 incoming freshmen was 4.19, with SAT scores at 2031.) As is the case with many other prestigious universities, the lack of qualified candidates from underrepresented populations keeps these numbers low. Although the Office of Equity, Inclusion, and Diversity’s mission is to “cultivate a welcoming and supportive environment that enhances success and advancement…regardless of personal experiences, values, and worldviews that arise from differences of culture and circumstance,” it faces much adversity from outside factors. These impediments include the barring of affirmative action due to Proposition 209 in 1996, lack of counseling in high schools, budget cuts, and the large, bureaucratic University of California system, which constructs and administers admissions policies and admissions.

The diversity department, instead, has focused its efforts on outreach. They carry this out through programs that focus on fostering a college-going culture and providing counseling and advice at Greater Bay-area high schools and community colleges, says Gibor Basri, vice chancellor for Equity and Inclusion, appointed in 2007.

“That’s an area where we see more hope in diversifying the undergraduate student body. The pool we are drawing from are people that have gathered up and are motivated to get into UC-Berkeley. That’s been an area of opportunity for us,” says Basri.

Meanwhile, Berkeley’s Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, formerly the Haas Diversity Research Center, provides an incomparable resource: an in-house diversity research facility.

Attempting to gather data to change policy and practices towards traditionally disenfranchised groups, as well as connect faculty over issues of diversity, Chancellor Robert Birgeneau launched the first diversity research effort in 2006. The Haas Institute focuses on research in education, health, democracy, disabilities, economic disparities, religious diversity, and LGBTQ issues.

“A major goal of this research initiative is to define issues of importance that cut across traditional academic divisions, and to try to foster conversations in research that are truly multi-disciplinary,” says Michael Omi, associate director of the Institute and associate professor of Comparative Ethnic Studies. “A second goal is to incentivize faculty to work with community partners, like a unified school district or disability activists. A third goal is to try to have a communications strategy that disseminates existing scholarly research to multiple constituencies and audiences outside the academy.”

Student Life and Diversity

At such a large university, students are offered extensive opportunities to cultivate relationships and express their thoughts and interests. The student government alone, founded in 1887, is given almost exclusive autonomy. Coupled with its almost $2 million budget, it is a force to be reckoned with on campus.

Berkeley counts more than 700 student groups, ranging from the social to political, including the Berkeley ACLU and The Berkeley Student Food Collective. More Berkeley students attend the Peace Corp than from any other university. There are a wide range of ethnic and cultural clubs on campus, although these have been criticized for segregating people by ethnic groups in the past.

For Basri, there are competing ideas of maintaining “safe spaces” on campus where people feel included and exposing

students to the benefits of diversity. However, he says “it’s not incompatible to both provide safe spaces and facilitate and encourage crosscultural interaction. We try to do both.”

Berkeley gained a reputation for student activism in the 1960s with the founding of the Free Speech movement in 1964, and vocal opposition to the Vietnam War throughout the ’60s and ’70s. In the highly publicized People’s Park protest in 1969, students and the school conflicted over use of a plot of land; the National Guard was called in and violence erupted. Today, protests, petitions, and presentations are not uncommon on campus, although the activism of yesteryear is often in contrast to today’s moderate and conservative voices (College Republicans maintains an active presence on campus) that coexist alongside traditional liberal leanings. (Occupy Berkeley is still active in the community.)

“We have a strong tradition of vigorous debate and student activism. I think our campus is quite tolerant of that debate. We just ask that folks follow the general guidelines that were set up as a result of the Free Speech movement,” says Basri.

This liberalism of the ’60s does carry over into attitudes towards traditionally ostracized groups. A proud LGBTIQQ community has a presence on campus, helping increase tolerance. The Queer Resource Center hosts many events throughout the year to support LGBT students. And while some prestigious institutions across the country are often criticized for being privy to the wealthy, more than a third of students receive Pell Grants at Berkeley. (Pell Grants are awards, not loans, which traditionally are given to low-income undergraduate students.) In fact, more than a quarter of students are first-generation college students. Diversity in terms of socioeconomic and LGBT status may be less visible, but is nonetheless alive and celebrated on campus.

Another instance of student autonomy on campus is the Berkeley Student Cooperative, an innovative residence program on campus. The Berkeley Student Cooperative (BSC) houses more than 1300 students who perform a minimal amount of work each week to keep rental costs down. Founded in 1933 during the Great Depression, the BSC now has themed houses, including an African American house and a vegetarian-themed house, Lothlorien Hall. The BSC claims author Beverly Cleary as a alum, who lived at Stebbins Hall in the ’30s.

Future of the School and Diversity

Many issues surround diversity and the future of diversity at the school.

Sixty-six percent of students have at least one parent born outside the U.S., according to some of the most recent data from Berkeley. Undocumented students have become one of the university’s newest concerns, as many have come forward through the passage of the California DREAM Act two years ago. The issue of African American representation and inclusion at the school is still an issue, one of the oldest in terms of diversity, while Native American and LGBTQ issues have also come up in recent years.

“As the conception of diversity broadens, we shouldn’t lose sight of where it started, and the fact that some of the initial issues are unresolved. But that doesn’t mean we don’t have the bandwidth to work on new issues as they arise. We have enough staff and people who care to pay attention to all of them,” says Basri. “Where there are issues of equity and inclusion, that’s where we ask ourselves, ‘How can we help with this?’”

Questions undoubtedly arise over how to leverage these groups and their array of concerns while moving forward with Berkeley’s overall goal: to educate and prepare students for careers and life after their education.

“Our mantra is ‘Access and Excellence.’ While we are suffering disinvestment by the state, we are trying to make up for that in other arenas,” says Basri. “We are mindful of not losing our public mission through all the changes. We believe that while things keep shifting around, we need to keep that goal in mind.”